Musakhan is the national dish of Palestine. It’s just a round piece of bread with chicken, onions, and a ton of sumac. That’s it! Simple but delicious. You eat it rolled up like a sandwich or flat like a pizza. When I eat musakhan I always think of my mom and aunts cooking it in huge trays, layer after layer. We’d sit and eat, drinking tea and Turkish coffee, playing card games. At times we’d even forget about the wall.

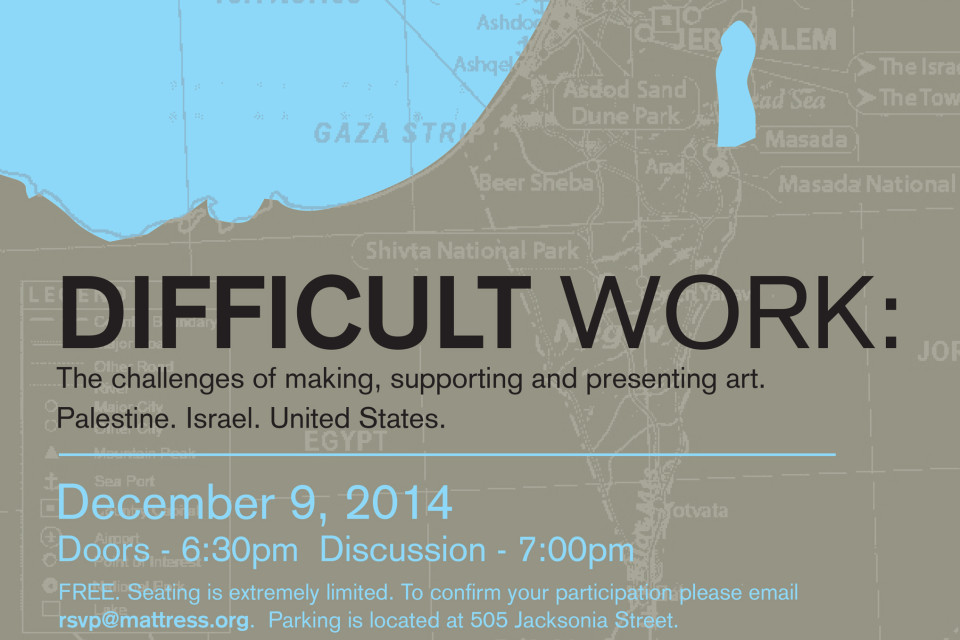

The Arab Bedouin culinary tradition centers around what’s available—goat, sheep, camel, and horse meat, as well as milk, cheese, and butter. The predominant dish among Bedouins in Syria, Jordan, and Palestine is something called mansaf, a mixture of lamb and garlic boiled in a fermented yogurt sauce called labne. In the old days, you could also get raw wheat from farmers, which was boiled with the mansaf. Nowadays we use rice, which is shipped in.

The new generation of kids don’t like the traditional food! Maybe when they get older. They like fried chicken—even Kentucky Fried Chicken.

Even though we’re only 10 or 15 miles from the sea, Israel lies in between, so people in the West Bank and Jordan are not really fish eaters. Our bay is called Al-Aqba; it’s too small to meet the needs of the people, so we have to import fish. One kilo of good fish costs seventy shekels–a whole day’s wage–and it’s probably only enough to feed one child. For this reason, people don’t really eat fish.